What is the Plastic Collective System?

Louise is a strong believer in resource not waste. We refer to something that cannot be recycled as waste – dirty nappies for example. Plastic however, has this incredible ability where it can be cleaned, reused and recycled numerous times before it’s value degrades. Louise avoids labeling plastics as “waste” but instead replaces it for terms such as “discarded plastic” or “fugitive material”. One of Plastic Collectives most important principles is changing people’s perception of plastic. If we treat plastic as a material then we can dissociate from that good/bad mentality, and instead focus on the actions and behaviours surrounding its usage, as well as its uses once recycled.

So once people see the value you see this big light come on, and suddenly people are empowered and can then see past the problem to the solution. That really is the essence of the system, that mindset change – we just provide the infrastructure, technology and training to help communities go through that.

Louise’s Big Idea

Plastic Pollution was an issue which resonated with Louise Hardman, Founder/CEO of Plastic Collective. Louise learnt a great deal about the reality of plastic pollution: finding that three quarters of the world’s plastic material was collecting and gathering in the asia-pacific region, learning that across over 4,000 islands there was no waste management systems to prevent plastic leakage, and over 370 million people lacked access to conventional waste management solutions. Having this knowledge and the will to make change, Louise had an idea: give plastic value. She believed through providing plastic materials with an increased value, plastic will be treated less like trash and more like treasure.

The idea gained traction when Louise attended the Our Ocean Conference, Bali 2018, and by pure chance ended up on a delegate ticket. “I was sitting just behind all these very important people – the President of Indonesia, Secretary of State John Kerry, Ellen MacArthur. This was where they launched the New Plastic Economy and the Global Commitment. The idea was to move to a circular economy and eliminate toxic plastics, and with it new designs for recyclable, biodegradable and compostable alternatives.

Shortly after, the 3R Initiative was born (Verra, Nestle, Danone) with its three key tenets: reduce, recover, recycle. One of the global commitments was that Nestle, Danone and Tetra Pak made a global commitment and set up the 3R Initiative, the Plastic Waste Reduction Standard. Plastic Collective joined this initiative, our project in North Bali became one of the 3R Initiative’s pilot programs.

Figure 1. Sorting plastic at the North Bali project – pilot program from the 3R Initiative

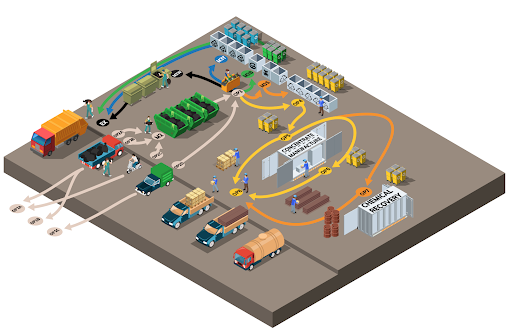

Hub and Spoke

Plastic Collective delivered three projects in three very different places – one in Queensland, another in a densely populated but remote area in North Bali, and one on a very small island off the coast of Borneo. The projects were a success and provided lessons for future endeavours: “The main thing was the machinery didn’t have the capacity to run as a financially sustainable business, but it was suitable for these smaller communities.”

The next challenge was moving the infrastructure to bigger models whilst also keeping that small community focus. “We started looking at increasing plastic capacity by increasing the area in which you collect from – so how do we do that? You start to collect materials from various sites in one centralised location, thereby creating a hub and spoke model.”

Louise explains that the idea of the Plastic Collective System really kicked into gear when they applied for a Cooperative Research Centres (CRC-p) grant. This allowed Plastic Collective to develop a system compared to just a singular machine which ran before. Louise and the team, now assessed every aspect of plastic pollution in diverse communities to create viable solutions based on an economical model.

Figure 2. The Shruder MK I – the first Shruder machinery

Figure 3. The Shruder MK II – increased shredding capacity

Figure 4. The Shruder MK I1 – training and education

Figure 5. The Shruder Recycling Station – design and planning

Working Together in Teams

After the CRC-p grant was approved, Louise emphasises that there were different working groups needed in order to get the system off the ground. The first group looked at the equipment itself, creating the Shruder Recycling Station as well as addressing all the other equipment and electrical items.

The second group included four scientists from Southern Cross University overseeing the product manufacturing. They assessed the machinery’s fire retardancy and investigated the most economical and/or profitable types of products that could be made by communities using the material that’s available to them. It also had to be simple to use and suit the Plastic Collective System.

With the assistance from the science team, Plastic Collective evaluated what type of manufacturing equipment would be required:

- press moulds,

- injection moulds,

- extrusion machines,

- as well as looking at the possibility of pyrolysis (turning the plastic into diesel fuel).

From the research, Plastic Collective devised the best solution was two machines, an extrusion machine and a press mould, that would be suitable, yet affordable.

The third unit, led by Plastic Collective’s Aly Khalifa, was responsible for creating the digital software to accompany and oversee the compliance aspect of the projects Plastic Collective undertakes. This was a key component to ensure the monitoring and recording of project compliance to the Plastic Waste Reduction Standard as well as Ethical and Environmental Compliance. Aly is developing a digital solution, including the development of an app which can track all the data related to the collection and recycling of plastics within projects.

Community engagement is Louise’s remit, and includes setting up a process to deliver projects, first through assessing their viability, then helping to design a system for communities that suits them, each one becoming very different.

“We thought we were going to have one system, but we quickly realised we can’t. There’s no ‘one size fits all’ approach.”

The training and education that Louise oversees now covers eight modules, split into three halves:

part a) Plastic Education,

part b) Project Preparation & Enterprise Essentials

part c) Operations Training

The idea with this is that the first part can be delivered to anyone, it’s an educational tool. Louise and her team have been working on the modules for over six years and it’s still a work in progress.

Figure 6. Community engagement within the Plastic Collective Bali project

Louise has the tough challenge of having to take quite complex things and make them simple and easy to understand across the various cultures Plastic Collective works with. Moreover, she ensures the information is safe, ethical and compliant.

“I had to rewrite our own plastic requirements, and then pull them all apart and break them down into different components.”

One such component is the social policy agreement, outlining best practices for staff. This is to ensure there is no child labour, and introducing equal fair play – all the things you should be doing.

Figure 7. Helping businesses to join the Plastic Credit Market

Tracking the Plastic

With the advent of plastic credits, it means that certificates can be generated to track the provenance of the recycled material. The collected plastic will be given two QR codes, the first at the collector where it gets dropped off, then a second one when the batch is ready to be processed through the baler. These two codes then link together, displaying where it came from to what it was recycled into. That code then gets attached to the bag, bale or product, and follows the rest of the supply chain. Once it gets bought, the buyer can scan it and go: ‘our friend picked that up on a beach, took it to the manufacturing place, where it was shredded, and turned into this product.’ With this comes a certificate, breaking down all the material types and features.

The plastic is also graded by its quality, ranging from A1 (which means that it’s clean and pure, with no other plastics in it), down to C, which is mixed and potentially dirty. For different products people will request different grades. For example, for an injection blow-mould they would need A1, whereas for a press mould to make a bollard they can use just about anything.

Figure 8. Using QR codes to follow the plastic’s cycle. From collection to remanufacture (Sea Communities).

Extending Partnerships with Local Businesses

Partnering with businesses and enabling enterprise to flourish form a key component to the success of the Plastic Collective System. Louise has found that many businesses are transitioning to more sustainable and environmentally friendly options. Plastic Collective receives countless emails everyday from businesses enquiring about using recycled plastic material from the ocean or environment. The general process from enquiry to reality goes a little something like this according to Louise:

“It requires a lot of questions to gain an understanding of exactly what the business would like to achieve and how. We have to say ‘Okay, if you want that certain material, do you want it from the ocean or do you want it from curb-side, and how much do you want?’ From there we have to assess their requirements and look at where we’re getting stuff from and say, ‘Okay, if we introduce just one more component, we can find a manufacturer who will pellitize it’. From there, we can pick it up, granulate it, process it, clean it, and then you’ve got the material to make your new product.”

Figure 9. Turning recycled ocean plastic in to WAW handplanes used in the ocean.