We talked to founder and CEO Louise Hardman about Plastic Collective’s latest community project in Java, Indonesia.

Like many places across the globe, discarded plastics are putting extreme stress on the natural environment, local communities and surrounding wildlife. Working with Plastic Collective’s collaborative partners, Louise and her team are currently designing and delivering a project in a remote area of East Java to alleviate damage caused by plastic packaging leakage into the environment and farming communities.

The images we see of plastic bottles infiltrating the local environment does not concern Louise the most though. “HDPE and PET bottles usually get snapped up pretty quickly by other recyclers, which end up in a recycling facility; then you’re left with the soft plastics, which are often the most dangerous thing left in the environment.” The soft plastics are the ones more likely to blow away and infiltrate multiple spaces: “it blows into waterways, it blocks drains, and it causes a lot of problems for nature, wildlife and people – it gets into the farmland, affecting the cattle and animals.” Soft plastic debris are a threat on multiple levels.

Why does Indonesia have a plastics pollution problem?

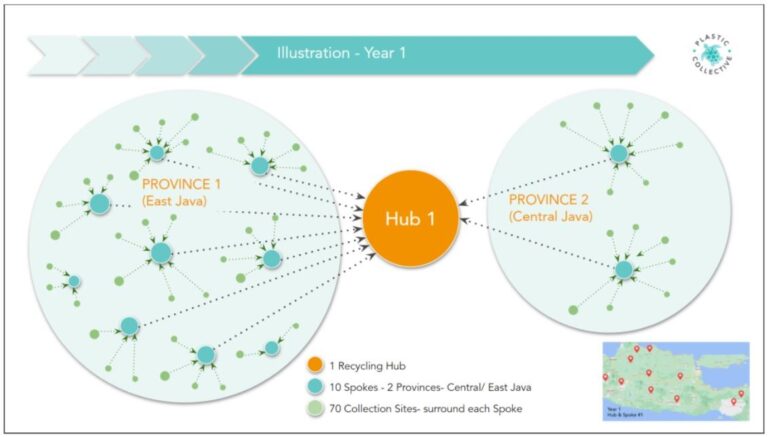

The crux of the idea is to operate recyclable plastic waste banks on a ‘hub and spoke’ model with the aim of collecting a minimum of 100kg of material a week. Louise explains: “the manufacturing hub is where all the raw material arrives, coming in from all the different waste collection sites (the spokes), and we build capacity from there.” Louise explains that essentially there are three stages to these recycling industry programs.

Figure 1: Plastic Collective’s Hub and Spoke Model

The first stage is recovery – that’s the collection and delivery to the site. The second is concentration, which is to reduce the volume of plastic materials into bales or shreds – this means it’s prepared to be processed and can be easily transported. And the third part is the recycling of the materials, where the plastic gets remoulded and transformed into other products. These three elements form the basis for a circular economy.

Louise explains that the problem is that this part of Indonesia has irregular collection services, leaving the onus on each household to deal with the discarded materials they produce instead of the Indonesian government. Although the average amount of plastic discarded (approx. 20kg/ person/ year) is considerably less compared with most Western countries (many of which discard 100kg of plastics / person / year), it unfortunately leaves most Indonesians with one of three options when it comes to its disposal. “Families either have to burn it, bury it or dump it. Many remote communities will generally rake all their plastic together with their leaves and burn it in their backyards. And other places will collect tonnes of plastic and dump it in unoccupied land or into rivers.” Properly managed landfills are just not yet part of local government waste management systems.

Why is Western Plastic Pollution ending up in Asia?

Aside from a lack of local infrastructure, Louise makes it clear that external influences have exacerbated Indonesia’s domestic problem with waste disposal. Over the last few decades the rest of the world was conveniently offloading its waste to China – until they shut the door in 2018. “China was getting fed up because…this rubbish was getting dumped into their cities and rural areas. Now their decision to clean up their country has exposed this massive global problem.” Since then, the issues of single-use plastic, ocean plastic and microplastics have dominated the global sustainability agenda.

Unfortunately, places such as Indonesia and Malaysia became the next dumping ground which included a lot of non-recyclable waste. Indonesia currently produces 6.8 million tons of plastic waste per year, with only about 10% of it ending up in recycling centers (source: Borgen Project). In countries like these that lack waste management infrastructure,“[t]hey open shipping containers filled to the brim with rubbish [from developed countries]. A black market was created where discarded materials were being dumped in towns – whole areas covered in plastic rubbish that previously went to China.”

After a backlash, many Western countries had to apologise and agree to deal with the waste themselves, Australia being one of them. Australia has created a National Plastic Action Partnership plan to boost industries domestically. This is good news for Louise and her team: “In Indonesia they need the infrastructure, education and training to be able to deal with the waste, and so this project will be a good way of being able to demonstrate how it can be done.”

Figure 2: A dump site in Les Village, Indonesia. This is one of the communities that Plastic Collective collaborates with.

How does Plastic Collective work with the community?

So, did the local people need convincing of a project such as this? In a nutshell, no. The local communities are enthusiastically embracing the project. “There are low levels of income and a lack of jobs in these communities”, Louise explains, “however, they’re very inventive and creative, and so know the value of things.” How does that translate exactly? “Well, they seek the value in all discarded materials. If they can cash plastics in, the whole community will make sure that they’ll collect them.”

From the way Louise explains the project processes in depth, it certainly looks like a colossal task putting all these elements together. Coordinating with the existing waste banks, local transportation services and other entities operating within the region – how does it all fit together, especially when you don’t live where the project is taking place?

One person in particular was instrumental in helping the project gather place, Lukman. After having visited the region in 2019, Louise was contacted by various people about the projects Plastic Collective was undertaking, Lukman being one of them. “He contacted me with a Plastic Action Network proposal where he wanted to set up a recycling program in Surabaya, but unfortunately there weren’t enough funds to do it. It’s a shame because it was a really good idea.” So, Louise and Lukman kept in contact, and when the Java project came up, it became clear that Lukman would be the key person in helping coordinate the project. Moving to the region meant that Lukman could move around the area and direct the development of the recycling hubs.

How is the Coronavirus pandemic and local challenges affecting the Java project?

Of course, projects don’t always go exactly according to plan. The impact of the Coronavirus pandemic last year meant Louise’s team, who are based in Australia, Singapore, Europe and North America, were unable to visit Java and the potential plastic waste sites. Lukman has been essential in coordinating the program on the ground with Plastic Collective. This part of Indonesia is currently a Covid red-zone, with cases rapidly increasing. Lukman is unable to leave the area he’s based in, but can move within limits.

Education seems to be the most prominent casualty of Covid; usually workshops would be carried out but a ban on group gatherings has meant that Louise’s team have had to rethink how they distribute information. Louise again points to Lukman’s responsibility as the main representative for this project: “he’s taking printed booklets to every person involved with the waste banks.”

Local considerations can also pose headaches. Louise outlines that choosing a suitable hub is where they’re up to in terms of progress, but that the one they had agreed was most suitable has encountered a stumbling block: “unfortunately, the man who runs this site is quite sick, with his wife reluctant to have machinery that could be noisy in their community.” The hesitancy regarding machinery can be felt within the wider community and it’s clear that adapting to the needs of the local community, the key stakeholder, is essential.

What does the future hold for the Java project and other Plastic Collective Projects?

In spite of all the potential issues, the project is gearing up to be a success. Do you see many similarities with other projects? “I can definitely see that communities feel an immense sense of shame at the amount of waste product that is around them, and how this can be transformed into pride once the right training, tools and equipment are put in place.” This pride is felt most by those at the bottom rung of society, “I’ve witnessed the poorest people as waste pickers, and after the project has been implemented, they become almost like the toast of the town, they’re really valuable people in their communities. So, there’s this pride, and it’s just incredible seeing their faces – I love it!”

Do you think projects such as this will inspire more recycling initiatives to pop up in the near future? “Yes, for sure. It’s all about demonstrating to people what the possibilities are and how the simple pieces of equipment required add value.” Louise explains that there’s a sliding scale of value of the waste: “it shows people that if you collect it, you get a certain amount for it, if it’s clean you increase your price for it, if it’s clean and baled you get even more for it, and so on.” And of course, the local community can repurpose the waste they’ve collected themselves into things like fence posts and irrigation piping to send water around local farms. “The possibilities of supporting these communities to create products for themselves are endless.”

Projects such as these are ambitious, but very, very rewarding. Collaboration is the key, Louise says. “We’re trying something a bit different, and it’s very much based on working with all organisational levels: with the community, with large corporations, with experts in plastic recycling, with manufacturers and with community groups.” Collaboration in order to create a project which empowers communities, cleans our ecosystem and is profitable. “That’s the key thing.”

Our purpose at Plastic Collective is to show people how to find value in plastics as a resource, to understand which plastics can be recycled or recovered, and provide solutions to eliminate those which can’t be, thus preventing disposal of plastics. This will create sustainable circular economies which no longer rely on the ‘take-make-dispose’ attitude.

For more information, please contact us today.