Photograph by Jordi Chias sourced from National Geographic.

“Marine litter has become a pervasive pollution problem affecting all of the world’s seas. It is widely documented that marine litter, in particular plastic, has negative impacts on marine wildlife, primarily due to ingestion and entanglement. Most cetacean species (more than 66%) are adversely affected by this pollution.” (Fossi et al, 2018)

MARINE SPECIES ENTANGLEMENT & INGESTION OF PLASTICS

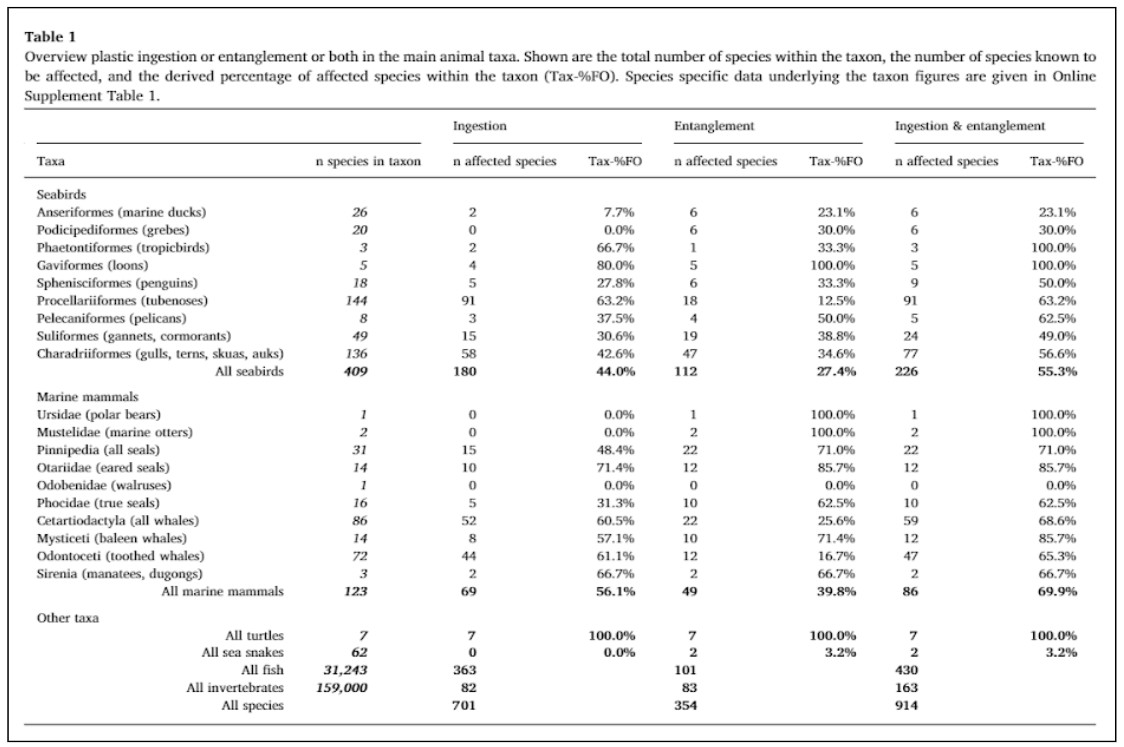

One of the latest 2020 studies from esteemed Kuhn and Frankeker underscores the threat marine debris is posing to marine life. According to the study, marine debris affected 914 species through entanglement (354 species) and/or ingestion (701 species).

Around 700 marine species are known to ingest pieces of plastic such as plastic bags and single-use plastics throughout the food chain. This includes half of the world’s cetaceans (such as whales and dolphins), all of its sea turtles and a third of its seabirds. This research review, entitled ‘Quantitative overview of marine debris ingested by marine megafauna’ found ingested plastics occurred in 701 species (see table 1. below).

Ingestion of plastics was recorded in the digestive system of 180 of the 409 species of seabird (44%), 69 of the 123 species of marine mammals (56%), and 7 out of 7 species of marine turtles (100%).

MARINE DEBRIS IS NOT A NEW CHALLENGE

The ingestion and entanglement of marine debris by marine species is not a new challenge. First-hand experience of marine animals’ fatal plastic ingestion was witnessed by zoologist Louise Hardman in 1993 in Coffs Harbour, Australia. At the time, Hardman was working as a Project Officer for the newly established Solitary Islands Marine Reserve by the Pacific ocean.

There, after rescuing a small, green turtle from the banks of Wooli River and taking it to the local marine conservation center (Pet Porpoise Pool), the turtle slowly died over 3 days (see Figure 1).

Hardman dissected the turtle and discovered 15 different types of plastic fragments in its gastrointestinal tract (see Figure 2). It is likely the plastic particles were caught in the seagrass, which the turtle was eating. Death was caused by a blocked intestinal system, multiple ulcerations of the stomach wall and prolonged starvation. For decades this story has repeated as marine organisms across the food chain and their marine ecosystems are increasingly infiltered by ocean plastic.

Determined to solve this problem in the marine environment, Louise started an environmental business in 2016 known as Plastic Collective. Exactly 25 years to the day, on 24th June, 2017, Louise won the Coffs Coast Startup Grand Prize with her invention of the Shruder – a mobile recycling unit to enable remote communities to transform tonnes of plastic trash and waste into resources, which prevents marine pollution. Hardman believes that only by properly monetizing waste plastic can marine fauna be saved. The impact on marine life has already affected human health too, such as how the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch” in the North Pacific Ocean has many tonnes of chemical plastic waste.

PLASTIC DEBRIS’ IMPACT ON WHALES

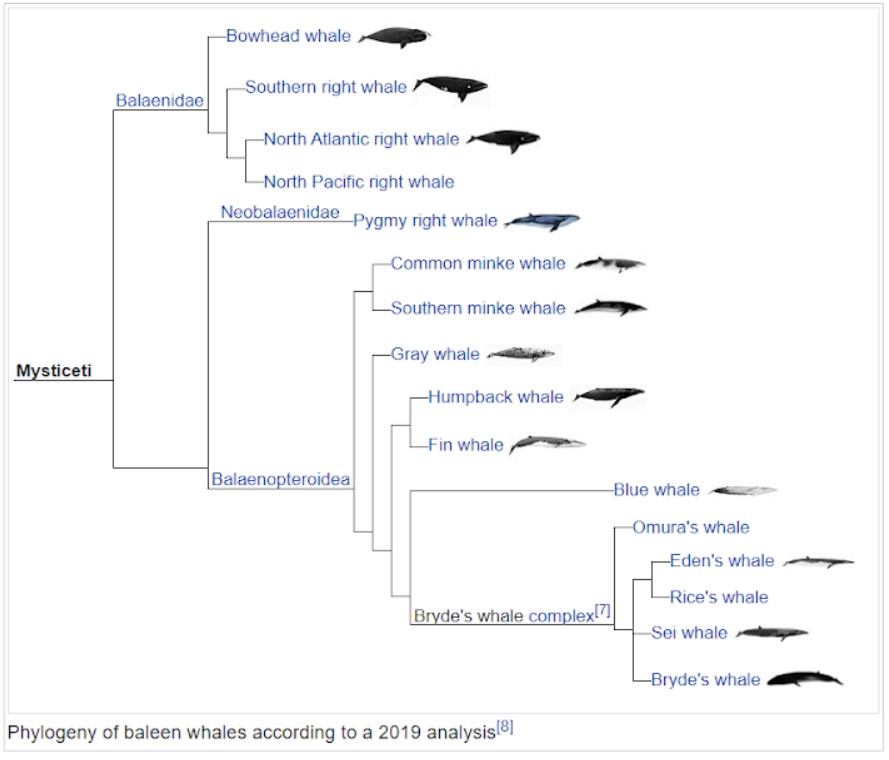

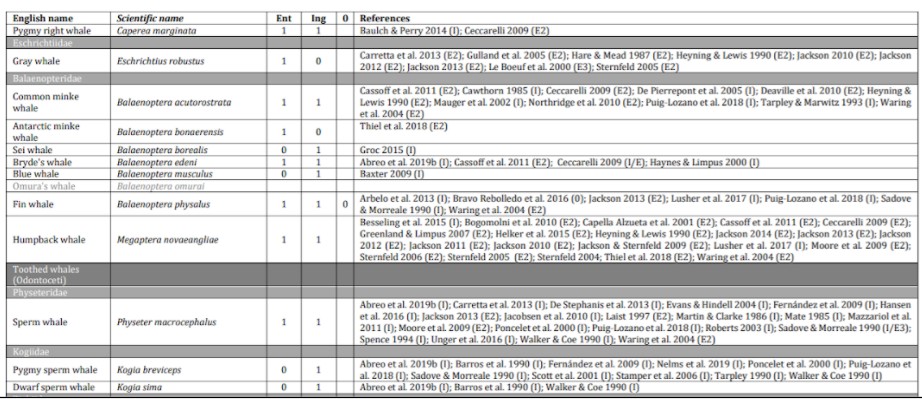

Kuhn & Frankeker’s 2020 research examined plastic ingestion in 8 of the 14 Baleen whale species (Mysticeti), which are all from the family group, Balaenopteridae or ‘Rorquals’ (figure 4.) This family includes Humpbacks, Blue, minke, Bryde’s, Fin and Sei Whales.

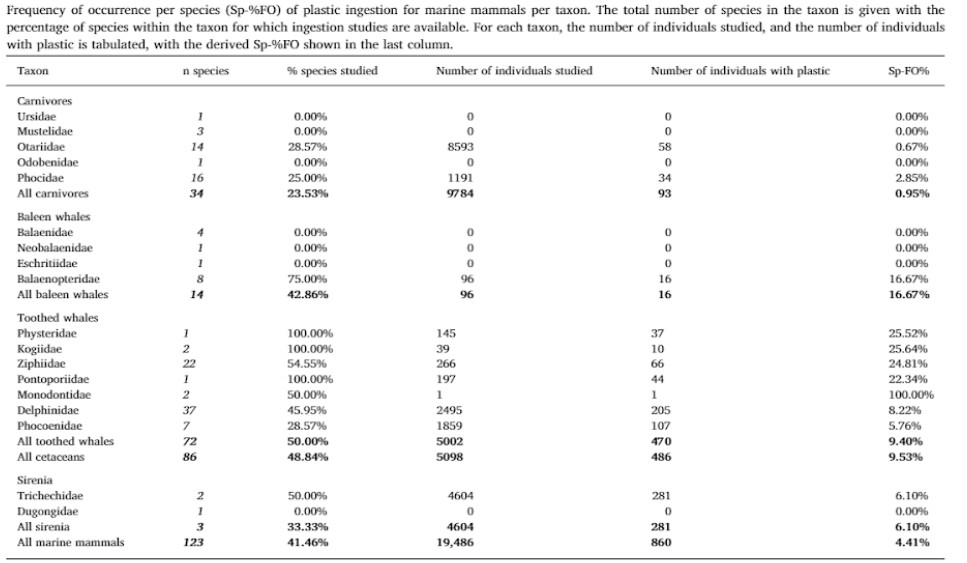

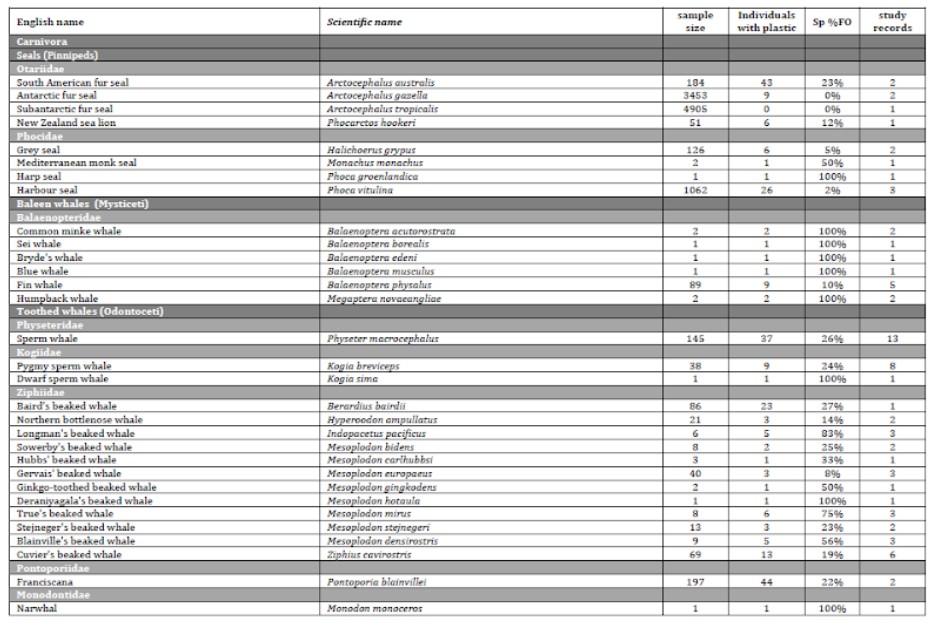

The research examined various marine megafauna (see Table 2 below) including carnivores (Polar bears, seals, otters), Baleen whales, Toothed whales and Sirenia (e.g., dugongs).

Of the 86 species of whales (‘all Cetaceans’), just under half were represented in the research (Kuhn & Frankeker, 2020). A total of 5,098 individual whales were studied. From this sample size, 486 whales were found with plastic pollution ingestion, representing 9.53% frequency of occurrence (%FO).

For the 14 species of Baleen whales, 8 included the Balaenopteridae whales (Humpbacks, Blue, etc.). Ninety-six individual whales were studied and 16 of these were found to have ingested plastics, including Humpback whales. The frequency of occurrence (%FO) in this group (16.67%) was the highest average for all of the Cetaceans, compared with Toothed whales at 9.4%.

Although some extreme cases of Sperm whales ingesting many large plastic products exist from recent studies (Jacobsen et al., 2010;De Stephanis et al., 2013;Unger et al.,2016), only Baleen whales show a higher frequency of occurrence, Sp-%FO (16.67%). This may be due to their feeding habits of ingesting large volumes of water to feed on small krill, which may also contain floating and suspended plastic from the ocean currents.

It is well documented that ingested plastics pollutants do not break down in the gastrointestinal tract of fauna, rather they can cause intestinal blockages, ulceration of the stomach lining and starvation (Roman et al, 2020). This is seen in marine turtles and other marine megafauna around the world’s oceans.

Below are the common and specific names of individual megafauna found with plastic ingestion/entanglement for Seals, Baleen and Toothed whales.

CENTRE FOR SUSTAINABLE SOLUTIONS

Plastic Collective and Miimi Aboriginal Corporation are combining forces for the health of the ocean, to protect and enhance marine life. By establishing a waste plastic resource recovery facility in Bowraville for the region. Marine debris and kerbside plastic material will be recovered and processed into valuable products. This will eliminate material from going to landfill and then escaping as runoff into waterways and the ocean.

Background on Miimi & Gaagal

The Gumbaynggirr nation covers a vast area estimated at 6,000 km2 on the Mid North NSW Coast, from Tabbimoble Yamba – Clarence River to Ngambaa – Stuarts Point, SWR- Macleay to Guyra and to Armidale.

Gumbaynggir people are often referred to as the ‘Saltwater People’, as their totem is ‘Gaagal’ – ‘Ocean’ in Gumbaynggir language. Their cultural responsibility and passion for protecting and caring for the health of the ocean is embedded deeply and across many generations.

Miimi (Mothers) Aboriginal Corporation was started by Aunt Ruth Walker, along with founding jinda’s (sisters) Rita and Florence Ballangarry, in the late 1980’s. It was at this time that they realised there was no support for Aboriginal women and families in Bowraville [Bawrruung]. With foresight, passion and energy they encouraged the community to realise their dream of developing programs and bringing services into the community for women and their families. Miimi is now run by Aunty Ruth’s daughter Patricia Walker.

In late 2019, Patricia Walker reached out to Plastic Collective to request a waste plastics recovery program for their region. Over the next few months, Plastic Collective and Miimi secured the old Bowraville Buttery site and started planning the establishment of a visionary ‘Centre for Sustainable Solutions’. The Centre provides local youth and families with new employment opportunities under the umbrella of Caring for Country – Sea and Land.

As this project grew, other stakeholders and local partnerships developed. Nowadays, this includes links to Bellwood Educational program, the newly formed Nambucca River Land and the Sea Rangers program. These partnerships are expanding the opportunities for the local indigenous community to become leaders in protecting waterways and oceans.

Together Plastic Collective and Miimi Aboriginal Corporation all share a unified vision of ‘Healthy Oceans’.

REFERENCES

Fossi et al, “Impacts of marine litter on cetaceans: a focus on plastic pollution, (2018)

Kuhn & Frankeker,”Quantitative overview of marine debris ingested by marine megafauna” (2020)

Roman et al, “Plastic pollution is killing marine megafauna, but how do we prioritize policies to reduce mortality?”, Journal of the Society of Conservation Biology, (2020)

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

*Besseling E, Foekema EM, Van Franeker JA, Leopold MF, Kühn S, Bravo Rebolledo EL, Heße E, Mielke L, IJzer J, Kamminga P (2015) Microplastic in a macro filter feeder: Humpback whale Megaptera novaeangliae. Marine Pollution Bulletin 95: 248-252 doi https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2015.04.007

Bogomolni AL, Pugliares KR, Sharp SM, Patchett K, Harry CT, LaRocque JM, Touhey KM, Moore MJ (2010) Mortality trends of stranded marine mammals on Cape Cod and southeastern Massachusetts, USA, 2000 to 2006. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 88: 143-155 doi https://doi.org/10.3354/dao02146

Capella Alzueta J, Florez-Gonzalez L, Fernandez PF (2001) Mortality and anthropogenic harassment of humpback whales along the Pacific coast of Colombia. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 47: 547-553

Ceccarelli DM (2009) Impacts of plastic debris on Australian marine wildlife, Consulting CR, Report for the Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, pp 83

Greenland JA, Limpus CJ (2007) Marine wildlife stranding and mortality database annual report 2007. Il. Cetacean and Pinniped, Environmental Protection Agency, pp 26

*Jacobsen JK, Massey L, Gulland F (2010) Fatal ingestion of floating net debris by two sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus). Marine Pollution Bulletin 60: 765-767 doi https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2010.03.008

Heyning JE, Lewis TD (1990) Entanglements of baleen whales in fishing gear off Southern California, 40th Report of the international Whaling Commission, Cambridge, pp 427-431

*Lusher AL, Hernandez-Milian G, Berrow S, Rogan E, O’Connor I (2017) Incidence of marine debris in cetaceans stranded and bycaught in Ireland: Recent findings and a review of historical knowledge. Environmental Pollution 323: 467-476 doi https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.09.070

Moore E, Lyday S, Roletto J, Litle K, Parrish JK, Nevins H, Harvey J, Mortenson J, Greig D, Piazza M (2009) Entanglements of marine mammals and seabirds in central California and the north-west coast of the United States 2001–2005. Marine Pollution Bulletin 58: 1045-1051 doi https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2009.02.006

Sternfeld M (2006) 2005 Alaska Region Marine Mammal Stranding Summary. National Marine Fisheries Service, Alaska Region, Protected Resources, Juneau, Alaska, pp 4

*Thiel M, Bravo M, Hinojosa IA, Luna G, Miranda L, Núñez P, Pacheco AS, Vásquez N (2011) Anthropogenic litter in the SE Pacific: an overview of the problem and possible solutions. RGCI-Revista de Gestão Costeira Integrada 11: 115-134

*Thiel M, Luna-Jorquera G, Álvarez-Varas R, Gallardo C, Hinojosa IA, Luna N, Miranda-Urbina D, Morales N, Ory N, Pacheco AS (2018) Impacts of marine plastic pollution from continental coasts to subtropical gyres—fish, seabirds, and other vertebrates in the SE Pacific. Frontiers in Marine Science 5: 1-16 doi https://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2018.00238

*Waring G, Pace R, Quintal J, Fairfield C, Maze-Foley K (2004) US Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico marine mammal stock assessments–2003. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NE 182: 287

[*Note: More references are available for other marine megafauna, if interested.]

Our purpose at Plastic Collective is to show people how to find value in plastics as a resource, to understand which plastics can be recycled or recovered, and provide solutions to eliminate those which can’t be, thus preventing disposal of plastics. This will create sustainable circular economies which no longer rely on the ‘take-make-dispose’ attitude.

For more information, please contact us today.